Typing reducers

Let's head back over to our Accident Counter and check out the use-reducer-base branch.

We've see how to use TypeScript with useState, but what about useReducer? It shouldn't be surprisng to find that a lot of it works out of the box, that said, there are still some additional features that we can take advantage of the make our lives easier.

Refactoring from useState to useReducer

There are a few ways that we could do this:

- Just create a super simple reducer that recieves a number and updates it accordingly. This is super similar to what we're doing with

useState. - Create and dispatch actions like we typically see when using

useReducer.

Since the goal it so get a deep understanding of how TypeScript works with React, let's try both, although you'll probably typically do the latter.

The simplest reducer

This will technically do the trick.

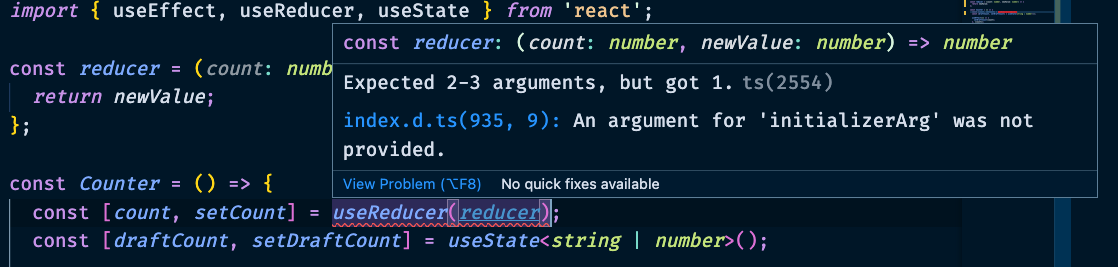

const reducer = (count: number, newValue: number) => {

return newValue;

};

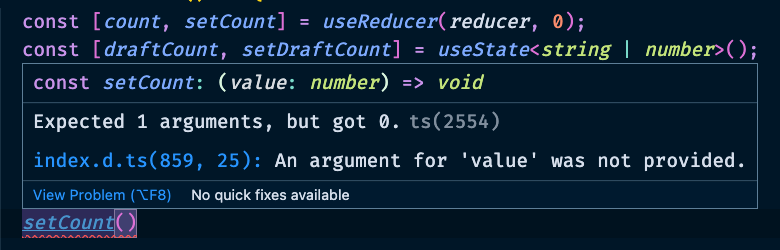

const [count, setCount] = useReducer(reducer, 0);

There are a bunch of ways this could go wrong. What happens if we don't pass our new setCount a value? What if we don't give useReducer a default value? These are all reasonable converns that TypeScript has as well. Luckily, it will automatically protect us from writing code that hits either of the afformentioned oversights.

Okay, enough of that. Let's write a real reducer.

Managing the current and draft count with the same reducer

Let's talk about what happens when we don't take advantage of TypeScript in this situation. Shall we? I didn't even do this on purpose, but I wrote up a super simple implementation to get us ready for this section.

You can find the code here, but I'll include some of it here too just for context. It's also available in on the use-reducer branch for this application's repository.

Here was my reducer:

type InitialState = {

count: number;

draftCount: string | number;

};

const initialState: InitialState = {

count: 0,

draftCount: 0,

};

const reducer = (state = initialState, action: any) => {

const { count, draftCount } = state;

if (action.type === 'increment') {

const newCount = count + 1;

return { count: newCount, draftCount: newCount };

}

if (action.type === 'decrement') {

const newCount = count - 1;

return { count: newCount, draftCount: newCount };

}

if (action.type === 'reset') {

return { count: 0, draftCount: 0 };

}

if (action.type === 'updateDraftCount') {

console.log('updateDraftCount');

return { count, draftCount: action.payload };

}

if (action.type === 'updateCountFromDraft') {

return { count: Number(draftCount), draftCount };

}

return state;

};

In the component itself, I wrote the following:

const Counter = () => {

const [{ count, draftCount }, dispatch] = useReducer(reducer, initialState);

return (

<section className="flex flex-col items-center w-2/3 gap-8 p-8 bg-white border-4 shadow-lg border-primary-500">

<h1>Days Since the Last Accident</h1>

<p className="text-6xl">{count}</p>

<div className="flex gap-2">

<button onClick={() => dispatch({ type: 'decrement' })}>

➖ Decrement

</button>

<button onClick={() => dispatch({ type: 'reset' })}>🔁 Reset</button>

<button onClick={() => dispatch({ type: 'increment' })}>

➕ Increment

</button>

</div>

<div>

<form

onSubmit={(e) => {

e.preventDefault();

dispatch({ type: 'updateCountFromDraft' });

}}

>

<input

type="number"

value={draftCount}

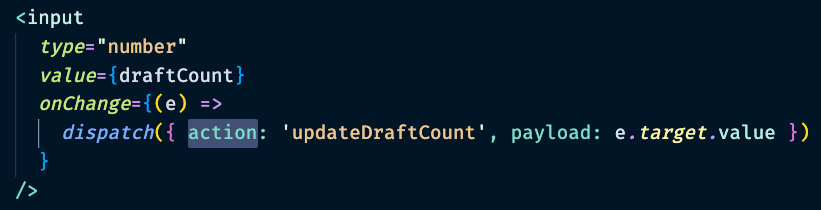

onChange={(e) =>

dispatch({ action: 'updateDraftCount', payload: e.target.value })

}

/>

<button type="submit">Update Counter</button>

</form>

</div>

</section>

);

};

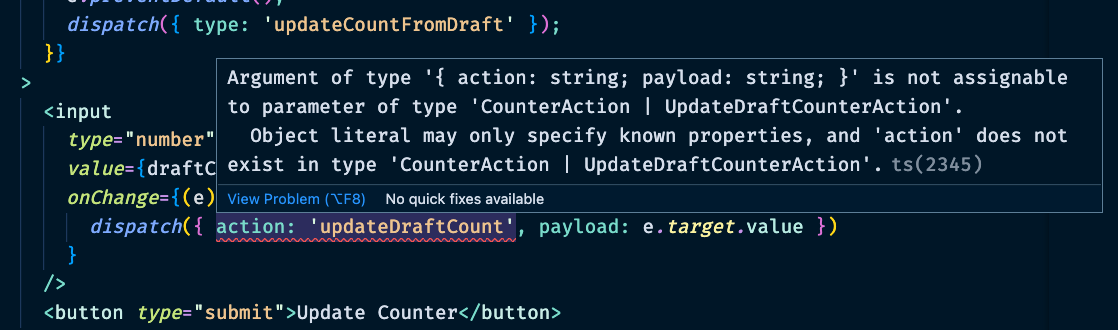

Enumerating my mistakes and other issues

To be clear, I was intentionally doing this the hard way to make a point—it just turns out that I did an even better job of making my point than expected.

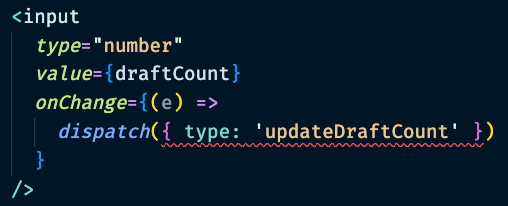

- Updating the draft count doesn't work because I made a typo. I called the property

actioninstead of countis a number, butdraftCountturned intoany.- This is because

actionis any and thedraftCountvalue comes into contact with myactionand thereby get's infected with itsany.

- This is because

There are other things that could have gone wrong. For example, I spent a few minutes and a bunch of console.logs checking to see if I had mispelled one of the action names—because, that's absolutely happened to me before.

It's kind of wild to see how one any could so wildly throw away all of the hard work we've done up to this point.

Refactoring our reducer

The name of the game is getting ready of that pesky any and then reaping all of the rewards for our hard work.

If an action is not any then what is it? Redux insists that action is an object and has a type property. As you saw with the simple example earlier, React's useReducer doesn't even care about that. It let us dispatch a number. But, let's set some ground rules and say we're going to follow something similar to Flux Standard Actions.

We'll say that at the very least, actions conform to this psuedocode interface:

interface Action {

type: string;

payload?: unknown;

}

Don't let that unknown scare you. This is just an example that we're not going to use. We'll bring this idea into reality in a bit, but let's solve the problem at hand first.

(If you really want to know what I would do. You can peek at this.)

Let's let this reducer know about what kind of actions it can expect. If we look, it's handling the following:

incrementdecrementresetupdateDraftCount(This one has a payload with the new value.)updateCountFromDraft

Let's start by taking care of all of the actions that don't take a payload first. One of the problems with the fictitious interface that I defined above is that we don't really avoid the problem of mistyping a type.

In JavaScript, we often see people use constants to get around this. If you misspell a string, the code still compiles; if you mispell a constant, everything blows up. That's one way to roll your own type safety, I suppose.

const INCREMENT = 'increment';

const DECREMENT = 'decrement';

I've always hated this. Next thing you know, you're importing these constants all over the place. It's just a mess.

Instead, let's try this:

interface CounterAction {

type: 'increment' | 'decrement' | 'reset' | 'updateCountFromDraft';

}

We're now saying that an action can't just have any strings. It has to have one of the types that we know about. In a similar fashion, we can tell TypeScript about updateDraftCount and what kind of payload it's expecting.

interface UpdateDraftCounterAction {

type: 'updateDraftCount';

payload: number | string;

}

Updating our reducer with the new action type

Let's get rid of that insipid any and replace it with our new types:

const reducer = (

state = initialState,

action: CounterAction | UpdateDraftCounterAction,

) => {

// …

};

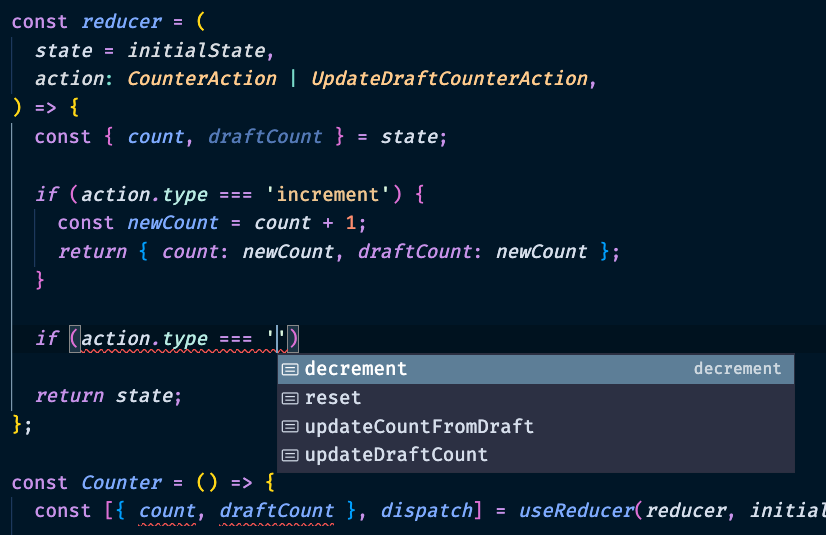

If you look closely, you can see that TypeScript saved me the trouble of logging to the console and immediate saw the error of my ways.

Taking advantage of the benefits

It gets even better, because now we have autocomplete for anything involving this reducer and its actions.

Let's imagine that I started with this approach and began to write my reducer with the type already defined.

There are two things to notice here:

- We get autocomplete.

incrementis not included in that list.

increment is not included because we already handled that case above. As you add additional cases, the list will get shorter and shorted.

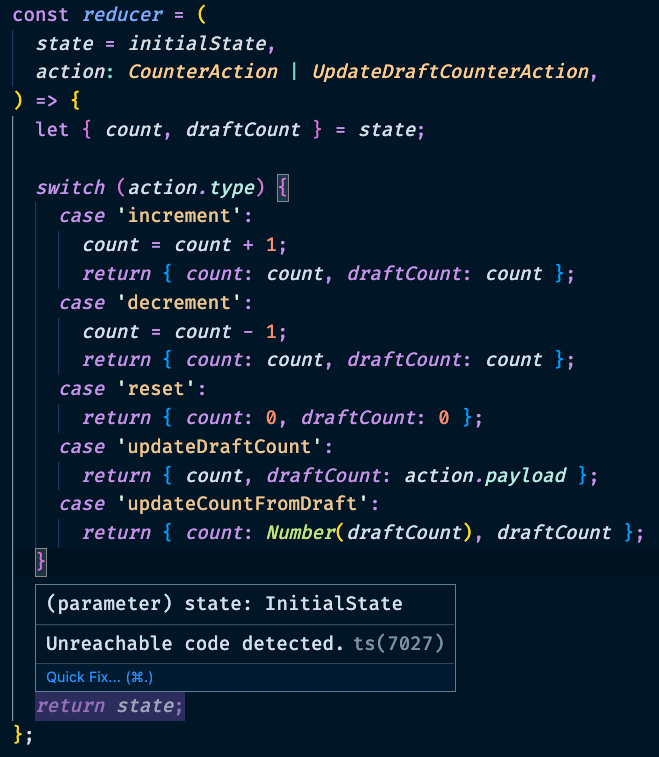

Usage with switch statements

As a matter of preference, I don't care for switch statements. But, there is something interesting to notice in the screenshort below.

You'll notice that return state is faded and TypeScript knows that we'll never reach that code because we've handled all of the possible cases an action.type can be. It also doesn't insist we have a default case for the same reason.

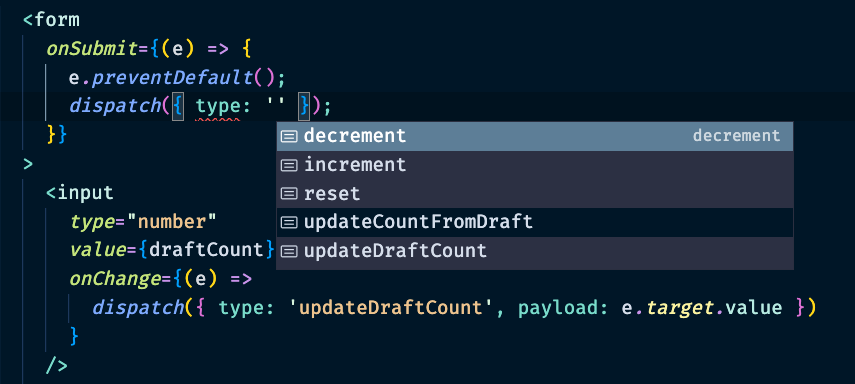

It will also help us as we use these actions in our components.

Additionally, if the action type expects a payload, TypeScript will ensure we don't forget about it.

Conclusion

Using TypeScript does add some additional work, but it also reduces—or maybe even—elimates the need for patters such as assigning action types to constants and action creators.

You'll also noticed that I took care of coercing the potential string to a number in the reducer and I no longer need that useEffect that I apologized for in a previous section.

You can see the end result here.